The Lentin Commission, officially known as the “Justice B. Lentin Commission of Inquiry,” was a pivotal investigative body established in response to a tragic incident at Mumbai’s JJ Hospital in 1986. Here is a detailed explanation of the Lentin Commission and its significance:

Background:

- Incident: In early 1986, 14 patients at the government-run JJ Hospital in Mumbai died under suspicious circumstances after consuming a routine medicine containing industrial glycol instead of glycerin, a deadly error.

- Exposure: Journalist Jagan Phadnis’ report in the Maharashtra Times brought the issue to public attention, triggering widespread outrage and demands for accountability.

- Formation: The Maharashtra government, responding to public pressure, appointed a commission of inquiry led by Justice B. Lentin, a sitting judge of the Bombay High Court.

Scope and Focus:

- Investigation: The commission was tasked with investigating the circumstances leading to the deaths at JJ Hospital, scrutinizing the roles of hospital staff, administrators, regulatory bodies, and suppliers.

- Duration: The commission’s proceedings extended for about one-and-a-half years, delving deep into the systemic failures and malpractices that contributed to the tragedy.

Key Findings and Revelations:

Facts of the Case: In January–February 1986, 14 patients well on the road to recovery in Mumbai’s government- run JJ Hospital suddenly died, showing identical symptoms after consuming a routine medicine glycerin (or glycerol), an anti-oedema drug used to combat swelling. The glycerin was laced with industrial glycol, a chemical which attacks the kidneys and kills quickly. These deaths may not have come to public notice but for the Maharashtra Times story on it, broken by journalist Jagan Phadnis. The public furor that followed compelled the Maharashtra government to announce the institution of an enquiry commission, led by a sitting judge of the Bombay High Court, Justice B. Lentin, and presumed that the matter would blow over. It did not, and for several years thereafter, the Justice Lentin Commission of Inquiry remained the focus of intense and unprecedented public and media interest.

In the introduction to the report of the commission, Justice Lentin wrote, ‘Little did the 14 persons who died in the JJ Hospital tragedy know that they would arouse an outcry of public indignation which would lay bare lack of probity in public life, malaise and corruption in high places indulged in contempt of the laws of God and man. All is over bar the shouting. It is time to pause and forage into the murky waters of lies, deceit, intrigue, ineptitude and corruption to salvage the truth which led to this ghastly and tragic episode.’

Unmasking Corruption: An In-depth Analysis of Public Health Systems: This report, made public in March 1988, after much prevarication by the state government, is the first official document of its kind providing a rare and detailed insight into the state of our public health system. Its pages describe the ‘ugly facets of the human mind and human nature, projecting errors of judgement, misuse of ministerial power and authority, apathy towards human life, corruption, nexus and quid pro quo between unscrupulous license holders, analytical laboratories, elements in the Industries Department controlling the awards of rate contracts; manufacturers, traders, merchants, suppliers, Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) and persons holding ministerial rank. None of this will be palatable in the affected quarters. But that cannot be helped’.

Administration Failures and Negligence on JJ hospital inquiry: The commission’s sittings, which ran on for one-and-a-half years, initially focused on the JJ Hospital staff. Inertia, lack of accountability, and total absence of communication were the hallmark of their functioning. It exposed the gross negligence of the top administration in withdrawing the killer drug, which continued to do the rounds in the wards for four days, even after some alert hospital doctors had sounded the ‘red alert’ on January 25, 1986 and identified the suspect drugs. The hearings revealed the archaic method of communication within the sprawling hospital, where even on a matter as vital as stopping a killer drug, the information was conveyed through a single, roving, handwritten circular. With record keeping in shambles the system of drug recall needed remodeling on an emergency footing, the com- mission noted.

Role of Hospital Administrators: Dwelling at length on the qualities and duties of top hospital administrators who had utterly failed in acting to stop the killer drug even after being informed about it in writing, Justice Lentin observed, ‘The success of any system must ultimately depend on the integrity and efficiency of those manning it, and if these attributes are found at the top, they must percolate downwards. It is here where the system has utterly failed, resulting in the kind of tragedy which struck the JJ Hospital.’

The Alpana Pharma Saga: The commission provided an important understanding of the drug purchase system followed in our public hospitals. Kept deliberately obtuse and secretive, its rules left to individual caprice, it facilitated racketeering and money-making right down the line, at huge public cost. The JJ Hospital tragedy took place because the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) granted an illegal license to Alpana Pharma, supplier of the killer drug glycerol, without ensuring that basic regulations were complied with. During the course of the hearings and even thereafter, one found that the name of Ramanlal Karwa and his brothers, the owners of Alpana Pharma worked like a ‘magic wand’—as Justice Lentin put it—in the corridors of power. (Even after the JJ Hospital tragedy and despite the commission’s strong indictment, the Karwa brothers continued to find favor as drug suppliers to public hospitals, using the simple expedient of starting a company with a new name.)

Corruption in Hospital Drug Procurement: Meanwhile, the members of the hospital’s drug purchase committee, which included hospital doctors and government departments, went out of their way to place the hospital’s drug supply order with Alpana Pharma, far exceeding the proportion allotted to them by the industries department in their rate contract. The quid pro quo was evident with the discovery of money placed by the drug supplier in the private bank account of committee members, as in the case of the hospital’s then head of pharmacology department.

Chem Med Laboratory Affair: Corruption in Drug Certification: The absence of checks to ensure that quality drugs reached the public was revealed with painful clarity during the commission’s investigations. At that time there were only four government-owned drug-testing laboratories in the country and in order to cope with the huge workload the government appointed ‘government approved’ private laboratories that certified the purity of drugs. One such was Chem Med Laboratory that certified Alpana Pharma’s killer glycerol as being of standard quality. This company enjoyed special protection of FDA officials who had been wined and dined by the owners. Even after its role in the JJ Hospital tragedy was known to them, the FDA indulged in a massive cover up to shield this company by raising ‘red herrings’ and leading investigators up the wrong path.

The Apex Laboratory Controversy: In the case of yet another firm, Apex Laboratory, 14 assistant chemist employees had complained to the FDA about the firm writing ‘false, incomplete, misleading and imaginary reports’ related to drug analysis tests, but the organization did not take action.

Debating Drug Purity: The Role of In-House Testing Labs: An issue intensely debated at that time, as an outcome of the commission’s hearings, was whether public hospitals as also drug manufacturers should set up in-house drug- testing laboratories to ensure drug purity. Although a mandatory precondition for issuing of a drug manufacturing license, the FDA did not insist on its implementation. Small drug manufacturers insisted that they could not afford it. The trouble, however, was that even large drug companies including multinationals that had in-house drug-testing laboratories produced substandard drugs and could not be trusted to voluntarily withdraw them from the market unless caught by the FDA and severely penalized, which the latter was not inclined to do.

The Murder Book: Unveiling FDA’s Oversight Failures: The fact that even ‘reputed’ drug companies were repeat offenders was discovered by Justice Lentin when he visited the FDA headquarters during the commission’s investigations and examined the FDA’s Register of Sub-Standard Drugs, which he dubbed ‘The Murder Book’. It revealed the FDA’s failure in prosecuting 582 grossly erring drug manufacturing concerns, whose drugs were found to be substandard, misbranded, or sub- therapeutic, the majority of which were termed as ‘life saving drugs’. Many of these ‘merchants of death’ were habitual offenders, having committed as many as 41 offences during the span of five months in 1986, but the FDA turned a blind eye. When questioned, FDA joint commissioner S. Dolas told the commission that ‘someone has to die first’, before the FDA could issue prohibitory orders against a firm.

Profits Over Patients: The Exploitation of Public Health: This pointed to the enormous scale on which the public health system had been reduced to a captive market for profit spinning, where human life was of least concern. An examination of this register or ‘murder book’, if monitored today, would clearly provide the clues we need to explain why despite the JJ Hospital tragedy no lessons have been learnt and killer drugs continue to stalk patients in both public and private hospitals.

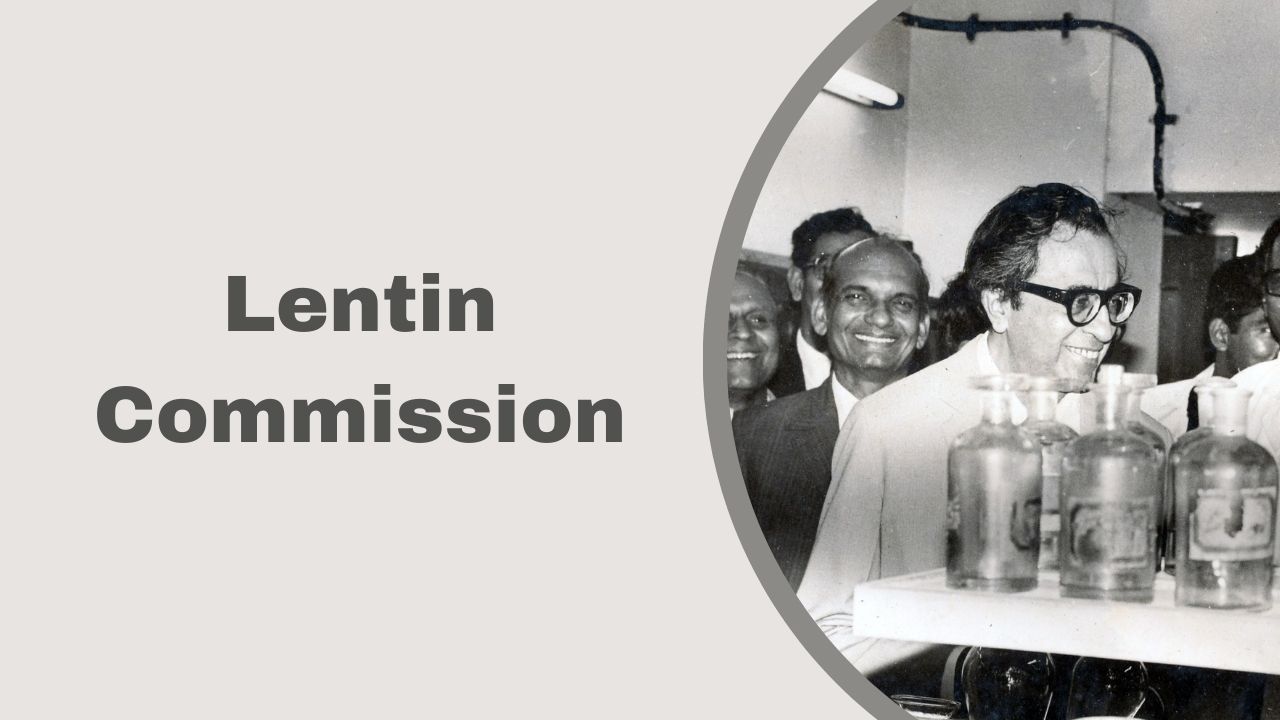

Exposing Corruption: Justice Lentin’s Inquiry into Sub-Standard Drugs: Justice Lentin and members of the Commission of Enquiry examining the Food and Drug Administration’s register of sub-standard drugs, or “murder book”. This and a multitude of such incidents uncovered by the commission revealed how the system of drug purchase and licensing was vulnerable to the pressures of vested interests. In consequence, the commission underlined that the cheapest-priced drug was not a criterion to guarantee quality drugs. It recommended scrapping of drug procurement through the rate contract system and reservation for backward areas. It instead suggested that government hospitals directly purchase their quota from reputed manufacturers and conduct their own tests to ensure standard-quality drugs, amongst other measures.

Political Interference Unveiled in the Commission’s Statewide Health Inquiry: Looking beyond the specific JJ Hospital episode, the commission then expanded its scope to a thorough probe into the state of the public health system in Maharashtra. Over 10 politicians which included health ministers past and present, MPs, and MLAs, were forced to reveal after much prevarication and loss of memory and when confronted with documentary evidence how their interference in the workings of the FDA had harmed public interest by the protection they gave to manufacturers of substandard drugs and destroyed the moral fiber of the FDA, reducing it to a ‘lapdog body’, according to the judge.

Ministerial Misconduct by Health minister Bhai Sawant: The Lentin report strongly indicted then health minister Bhai Sawant who was charged with gross ministerial interference, favoritism for extraneous considerations, and misuse of power, while irresistible inference of corruption was also drawn against him. It recommended an Anti-Corruption Bureau investigation against him as also former health minister Baliram Hiray, who was similarly indicted.

Political Nexus Exposed: Bhau Saheb Hiray Smarnika Samiti Trust: The commission found that the ‘government machinery was utilized by these politicians to extort money from the drugs industry to inflate the coffers of private trusts with which the ministers were associated.’ Dr Hiray was hard pressed to explain to the commission how the Bhau Saheb Hiray Smarnika Samiti Trust had received a large number of donations from beer bars, distilleries, and liquor vendors from all over Maharashtra as well as several hundred pharma concerns, including multinationals, which fell within his jurisdiction as minister. He had also assisted the trust in acquiring government-allotted land in Bandra, measuring 1,927 square meters at a throwaway price of Rs3.49 lakh.

Regulatory Failures: Uncovering the FDA’s Role in Drug Quality Control: The findings of the Lentin Commission are important not just for Maharashtra’s public health system but also for other states, as the majority of the drugs produced in India are manufactured in Maharashtra and patients from across the country come here for tertiary treatment. The commission found that far from regulating and imposing standards on the drug industry, the FDA had willfully allowed substandard drugs to be sold in the market. The commission undertook a detailed investigation into the manner in which the FDA functioned, both in terms of licensing and controlling the standard of drugs produced. The licensing of the then Rs2,000 crore drugs industry in Maharashtra was solely handled by the FDA joint commissioner and licensing authority, who was answerable to none but the health minister. This official handled all applications for licenses and had the power to refuse or grant them. He was also responsible for launching prosecutions against offenders amongst drug manufacturers. These untrammeled powers that he enjoyed could only be challenged in an appeal to the health minister.

Rampant Corruption in Drug Regulation: In the hands of unscrupulous Joint Commissioners and Licensing Authority, it could be an instrument of harassment and a device to make vast sums of money. This added to the inducements of the manufacturer of substandard, spurious and misbranded drugs and total lack of fear of the consequences pro- vided by the Act and Rules.’ the judge stated.

Political nexus with Joint Commissioner of FDA: Dividends came to those FDA officials who said ‘Yes Minister’ promptly enough. Their talent lay in wresting donations from the profit-spinning pharma companies which swelled the coffers of the private trusts controlled by ministers. It was this talent that enabled officers like S.M. Dolas, the FDA joint commissioner and sole licensing authority in the state to thwart every transfer order, supported as he was by a galaxy of politicians, thereby enabling an uninterrupted 20 year posting in Mumbai. Politicians stepped in to cancel every transfer made on Dolas since 1978 and overruled adverse reports made against him by successive FDA commissioners.

Challenges to India’s Pharmaceutical Reputation: India’s hard-earned reputation as one of the top-ranking global producers of medicines continues to take a beating for its inability to tackle this nexus of corruption as highlighted by the Lentin Commission. While the government has moved to decentralize the powers of the licensing authority, the FDA is still unable to perform its role as a watchdog. A policy brief published by The Foundation for Research in Community Health on ‘Accessing Medicines in Africa and South Asia (July 2013) states: ‘Its (Indian government) failure to establish a strong drug regulatory mechanism is casting doubt on the safety and quality of Indian drugs. With complaints of sub-standard drugs coming from major international buyers the US, Uganda, South Africa, there is deep concern within the Indian pharmaceutical industry that the ‘black sheep can tar the credibility of the entire industry’. The country’s pharmaceutical industry today valued at Rs.1,00,000 crore is seeing a rapid growth at approximately 10 per cent per year. It meets 95 per cent of the domestic needs and has a 10 per cent share by volume in the global market.

Calls for Regulatory Reform: Some key thinking emerging from the debates of that time is that the government will not be able to stem such tragedies unless it addresses itself to two tasks. To begin with in the short term, given Indian conditions where we contend with an irresponsible pharmaceutical industry and an inadequate vigilance machinery there is need for stiff penal action against errant manufacturers (which includes FDA confiscation of machinery and property in extreme cases) and prevention of cases from languishing in the courts. Evidence shows that even these measures come to ought in the absence of strong political commitment to weed out corruption and disallow the shielding of politician cronies.

Long-Term Solutions for Drug Regulation: In the long term, many see that the only solution lies in curbing the number of drugs, reducing them to the 270 basic drugs recommended by the WHO (World Health Organization). This was also endorsed by the Hathi Committee and former FDA com- missioners who agree saying there is a definite advantage in this. Several consumer and medical bodies have asserted the need to start by weeding out drugs banned the world over, but continue to be manufactured and sold in India, in some cases even in defiance of the ban order of the Drug Controller of India, under the shield of court-granted stay orders.

Promoting Generic Drug Usage and Health-Centric Practices: Also highlighted is the need to use drugs by their generic rather than brand names, which would curb their proliferation and bring down prices. They have also stressed the uselessness of cough mixtures, tonics major money spinners for the industry which can be effectively and cheaply substituted by a balanced food diet. Such measures would enable the medical and pharmaceutical industries to get back to their role of creating health rather than merely selling drugs.